Wawel Dragon

| Smok Wawelski | |

|---|---|

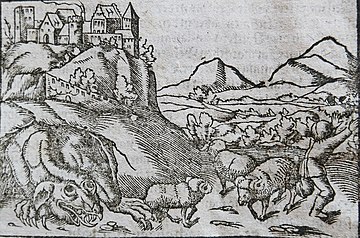

The Wawel Dragon, in Sebastian Münster's Cosmographie Universalis (1544) |

The Wawel Dragon (Polish: Smok Wawelski), also known as the Dragon of Wawel Hill, is a famous dragon in Polish legend.

According to the earliest account (13th century), a dragon (holophagos, "one who swallows whole") plagued the capital city of Kraków established by legendary King Krak (or Krakus, Gracchus, etc.). The man-eating monster was being appeased with a weekly ration of cattle, until finally being defeated by the king's sons using decoy cows stuffed with sulfur. But the younger prince ("Krak the younger" or "Krak junior") murdered his elder brother to take sole credit, and was banished afterwards. Consequently Princess Wanda had to succeed the kingdom. Later in a 15th-century chronicle, the prince-names were swapped, with the elder as "Krak junior" and the younger as Lech. It also credited the king himself with masterminding the carcasses full of sulfur and other reagents. A yet later chronicler (Marcin Bielski, 1597) credited the stratagem to a cobbler named Skub (Skuba), adding that the "Dragon's Cave" (Polish: Smocza Jama) lay beneath Wawel Castle (on Wawel Hill on the bank of the Vistula River).

Literary history

[edit]The oldest known telling of the story comes from the 13th-century work attributed to Bishop of Kraków and historian of Poland, Wincenty Kadłubek.[1][2]

Polish Chronicle (13th c.)

[edit]According to Wincenty Kadłubek's Polish Chronicle, a dragon appeared during the reign of King Krak (Latin: Grakchus,[3][4] recté Gracchus[5][6]).

St. Wincenty's original Latin text actually refers to the dragon as holophagus'[7] (Polish gloss: całożerca, wszystkożerca;[8] "one who swallows whole"), which was a neologism he had coined.[9] In Polish translation of the work, the monster is rendered as the "greedily swallowing dragon" (Polish: chciwie połykał smok).[10]

It was a "terrible and cruel beast" dwelling "in the depths [windings/curves] of a certain rock (scopulus)"[7][11] or emended to "a certain cave (spelunca)"[12] according to Wincenty.[a]

The dragon required a weekly offering of cattle, or else humans would have been devoured instead. In the hope of killing the dragon, Krak called upon his two sons[b]. They could not, however, defeat the creature by hand, so they came up with a trick. They fed him a cattle skin stuffed with smoldering sulfur, causing his fiery death.[13] After the success, the younger prince (referred to as the "junior Gracchus"; Latin: iunior Gracchus var. minor Gracchus,[15] i.e. Krak II; Polish: młodsy Grakus[10]) kills his elder brother blaming the dragon for the death. But his crime was soon revealed, and he got expelled from the country. Afterwards Princess Wanda had to accede to the kingship.[16][17][4][14]

Derivative chronicles

[edit]Among later chronicles derived from Wincenty Kadłubek's work, Chronicle of Greater Poland (<1296)[c] fails to make mention of the dragon at all, while the Dzierzwa Chronicle (or Mierzwa Chronicle; Kronika Dzierzwy/Kronika Mierzwy, 14th century) followed closely after Wincenty.[18] Both these chronicles maintain that Krak, Jr. is the younger prince, and keep the elder brother nameless.[13][14]

Jan Długosz's 15th-century chronicle,[19] however, swapped the roles of the princes, claiming that the younger son named Lech was the killer, while the elder son named Krak, Jr. became the victim.[14][18] The idea for the scheme to slay the dragon (olophagus) is credited to King Krak himself, not his sons, because the king fears a mass exodus from the city may take place,[20][18] and he orders to have the carcass stuffed with flammable substances, namely sulfur, tinder (Polish: próchno; Latin: cauma[d]), wax, pitch, and tar and set them on fire.[1] The dragon ate the burning meal and died breathing fire just before death. Długosz also adds the detail that the dragon lived in a cave of Mount Wawel upon which King Krak had built his castle.[20][18][e] In any case, the fratricide is banished, so their sister Princess Wanda must accede to the throne.[14]

Shoemaker version

[edit]

Later, Marcin Bielski's Kronika Polska (1597)[f] gave credit to Skub or Skuba the Cobbler (Skuba Szewca)[g] for designing the plan to defeat the dragon.[22][23][h] The story still takes place in Kraków during the reign of King Krak, the city's legendary founder, who is here called "Krok". The dragon required a diet of three calves (cielęta) or rams (barany), something in threes, and would snatch people to sate his hunger. On Skub's advice, King Krok had a calf's skin filled with sulfur, used as bait to the dragon. The dragon was unable to swallow this, and drank water until it died. Afterwards, the shoemaker was rewarded handsomely.[i] Bielski adds, "One can still see his cave under the castle. It is called the Dragon's Cave (Smocza Jama)".[j][24][25]

Popular retellings

[edit]The most popular, fairytale version of the Wawel Dragon tale takes place in Kraków during the reign of King Krakus, the city's legendary founder. Each day the evil dragon would beat a path of destruction across the countryside, killing the civilians, pillaging their homes, and devouring their livestock. In many versions of the story, the dragon especially enjoyed eating young maidens. Great warriors from near and far fought for the prize and failed.[26] A cobbler's apprentice (named Skuba[27]) accepted the challenge. He stuffed a lamb[27][26] with sulphur and set it outside the dragon's cave. The dragon ate it and became so thirsty, it turned to the Vistula River[26] and drank until it burst. The cobbler married the King's daughter as promised, and founded the city of Kraków.[27][26]

Dratewka

[edit]It has also been claimed that the name of the shoemaker is Dratewka in children's literature or storytelling about the Krak legend.[28] However, "Shoemaker Dratewka" (Polish: Szewczyk Dratewka) or the "Twine the Shoemaker"[29][k] is the name of the smok-slaying protagonist in Maria Kownacka's play O straszliwym smoku i dzielnym szewczyku, prześlicznej królewnie i królu Gwoździku ("The terrible Dragon, the brave Shoemaker, the beautiful Princess and King Gwoździk", 1935).[31] The hero of the same name (Szewczyk Dratewka) also appears in fairy tales by Janina Porazińska.

Origin theories

[edit]- Parallels

Legends of the Wawel dragon have similarities with the biblical story about Daniel and the Babylonian dragon,[32][33] and in fact, it was stated in the tract from the Dzierzwa/Mierzwa Chronicle that "Krak[us]'s sons killed the local dragon, like Daniel killed the dragon of Babylon".[34][20][35]

The tale of Alexander the Great's dragon-slaying using sulfur in the Romances on King Alexander (which episode only survived in the Syriac version, 7th century), bear an even closer resemblance.[l][37][38][39]

- Ancient myth

The legend of the Kraków dragon may well have ancient, pre-Christian origins. An allusion to the practice of Human sacrifice as part of an older, unknown myth has been suggested by historian Maciej Miezian.[40] Or perhaps an Indo-European myth of good vs. evil may underlie the legend.[41] The Kraków Dragon may well be interpreted as a symbol of evil has been commented by others[42]

- Historical bases

There might also be some echoes of historical events. According to some historians, the dragon is a symbol of the presence of the Avars on Wawel Hill in the second half of the sixth century, and the victims devoured by the beast symbolize the tribute levied by them.[43] The dragon may have represented the historical Bolesław II who was responsible for the martyrdom of St. Stanislaus of Szczepanów, bishop of Kraków, according to historian Czesław Deptuła.[44][45]

These ideas combined (the mythos may have been overlaid with a historical allegory) has also been described. The legend may be based on an Indo-European ur-myth about a thunder deity vanquishing a great serpent, and the serpent myth was possibly conflated with the cult of St. Stanislaus.[4]

Monuments

[edit]

The Wawel dragon's supposed Dragon's Cave (Smocza Jama) below Wawel Castle still exists, on the property on the edge of the Vistula River, and can be visited.[46] This particular cave was purportedly first described c. 1190,[47] i.e., in the first account of the legend by Wincenty, though the chronicler merely stated that the beast resided in a "winding of a rock (scopulus anfractibus)",[7][11] i.e. " a cave (spelunca)".[12]

A metal sculpture of the Wawel Dragon, designed in 1969 by Bronisław Chromy, was placed in front of the Dragon's Cave (Dragon's Den) in 1972.[48] The dragon has seven heads, but frequently people think that it has one head and six forelegs. To the amusement of onlookers, it noisily breathes fire every few minutes, thanks to a natural gas nozzle installed in the sculpture's mouth.

The Wawel Cathedral features a plaque commemorating the dragon's defeat by Krakus, a Polish prince who, according to the plaque, founded the city and built his palace over the slain dragon's cave.

In front of the entrance to the cathedral, there are bones of whales or Pleistocene creatures hanging on a chain, which were found and carried to the cathedral in medieval times as the remains of a dragon.[49] It is believed that the world will come to its end when the bones will fall on the ground.[citation needed] The street leading along the banks of the river leading towards the castle is ulica Smocza, which translates as "Dragon Street".

Dragon in culture

[edit]- Wawel Dragons (Gold, Silver, Bronze Grand Prix Dragons and Dragon of Dragons Special Prize) are awards, usually presented at Kraków Film Festival in Poland

- The Dragon (as "The Beast of Kraków") appeared in the eighth issue of a comic book series Nextwave from Marvel Comics (written by Warren Ellis and drawn by Stuart Immonen).

- The Dragon appears in a series of shorts produced and published by Polish company Allegro. The shorts re-visit classic Polish legends and folk tales in modernised form: in the first short, titled Smok, the dragon is presented as a flying machine used by a mysterious outlaw to capture Kraków girls.

- Wawel Dragon is also one of main characters in Stanisław Pagaczewski's series of books about a scientist Baltazar Gąbka, as well as short animations based on them.

- An archosaur discovered in Lisowice in 2011 was named Smok wawelski after the dragon.

- The Dragon was the mascot of popular Polish radio station RMF FM, and featured in its logo between its launch in 1990 and 2010. It was dubbed "Matilda", in honor of the daughter of one of the station's first journalists.[50]

- Andrzej Sapkowski's The Witcher story "The Bounds of Reason" begins with a cobbler attempting to slay a dragon by using a sulfur-filled lamb. Unlike in the Wawel Dragon myth, this attempt injures the creature but does not kill it.

See also

[edit]- List of dragons in mythology and folklore

- al-Mi'raj

- Esfandiyār (Isfandiyar)

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Ćwikliński ed. (1878), p. 607, Chronicon Polono-Silesiacum (c. 1895) appends spelunca (cave) in parentheses, calling the beast olofagus [sic.]: "Erat enim in cuiusdam spelunce scopuli anfractibus monstrum atrocitatis immanissime, quod quidam olofagum dicunt".

- ^ Wincenty only names the younger son as "the younger Krakus".[13][14]

- ^ Possibly attributable to Janko z Czarnkowa (ca. 1320–1387)

- ^ A scholium on a 16th cent. manuscript glosses cauma as "fomes", "zagyew".[21]

- ^ And exactly 3 beasts per day (tria singulis diebus belluae iactantur) needed to be delivered to the dragon according to Długosz.[18]

- ^ This is posthumous publication; the revisions to the Wawel dragon story are actually attributed to his son Joachim Bielski.[22]

- ^ The actual name is Skub (genitive Skuba) in the original writing, but later writers altered it to Skuba (genitive Skuby).[22]

- ^ The inspiration for the name of Skuba was probably a church of St. Jacob (pol. Kuba), which was situated near the Wawel Castle. In one of the hagiographic stories about St. Jacob, he defeats a fire-breathing dragon.[citation needed]

- ^ Polish: "Kazał tedy Krok nadziać skorę cielecą, siarką a przeciw iamie położyć rano: co uczynił za radą Skuba Szewca nieiakiego, ktorego potym dobrze udárowal y opatrzył"". King executed the plan, and Skub the Cobbler was rewarded (underlined portion).

- ^ Polish: "Jest ieszcze jego iama pod zamkiem, zowią Smoczą iamą", end of quote, Plezia (1972), p. 24. Photo of the cave appears on Fig. 6.

- ^ Glossed as the diminutive of dratwa 'twine"; dratewka a 'small, thin shoestring [Schuh-Drath, Schuhdrat] '.[30]

- ^ Comparison is also made to the account in Qazwini that Alexander's dragon-slaying was rewarded with gifts such as the horned hare, al-Mi'raj.[36] Hasluck (op. cit.) draws additional parallel with the story of Isfandiyar's dragon-slaying in the Shahnāma, though this is only "somewhat similar stratagem" as it involves daggers rather than sulfur.[32]

References

[edit]- Citations

- ^ a b Sikorski, Czesław (1997), "Wood Pitch as Combat Chemical in the Light of the Jan Długosz's Annals and Some of the Old Polish Military Treatises", Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Wood Tar and Pitch: 235, ISBN 9788390058634

- ^ Wincenty Kadłubek, "Kronika Polska", Ossolineum, Wrocław, 2008, ISBN 83-04-04613-X

- ^ Plezia (1972), pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b c Siama, Monika (2008). "Le palimpseste hagiographique de la Pologne du haut Moyen Âge : l'espace et le temps du culte de saint Stanislas de Szczepanowo". Revue des études slaves. 79 (1/2): 35–52. doi:10.3406/slave.2008.7124. JSTOR 43271841.

- ^ Kalik, Judith; Uchitel, Alexander (2018), Slavic Gods and Heroes, Routledge, ISBN 9781351028684

- ^ Nungovitch (2018), p. 281.

- ^ a b c Kadłubek (1872), p. 256: Erat enim in cuisdam scopuli anfractibus monstrum atrocitatis immanissimae

- ^ Bielski, August ed., Kadłubek (1872), annotated index, p. 451.

- ^ Kalik & Uchitel (2018).

- ^ a b Kadłubek (1862), p. 43.

- ^ a b Nungovitch (2018), p. 283: "terrible and cruel beast" dwelling "in the depths of a certain rock"

- ^ a b Węclewski ed. (1878) Chronica principum Poloniae, p. 430, n. 5: "W. Chr. Pol.: Erat enim in cuiusdam spelunce.."

- ^ a b c Wincenty Kadłubek; translated into English (excerpt) by Kalik & Uchitel (2018), based on Wincenty Kadłubek (1992) Kronika polska, Kürbis, Brygida (tr.), Wrocław, (in Polish).

- ^ a b c d e Schlauch (1969), p. 262.

- ^ Kadłubek (1872), p. 256, note.

- ^ Kadłubek (1862), pp. 42–43, Józefczyk tr., pp. 42–43 (in Polish)

- ^ Nungovitch (2018), p. 283.

- ^ a b c d e Rajman (2007), p. 39.

- ^ Długosz, Jan (1873). "Graccus arcem et civitatem Cracoviensem aedificat, et draco ingens latitans sub arce, incolis onerosus, occiditur". Joannis Długossii seu longini canonici Cracoviensis Historiae Polonicae libri XII. Vol. 1. ex typographia Kirchmayeriana. pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b c Schlauch (1969), p. 261.

- ^ Długosz, Jan (1964). "Graccus arcem et civitatem Cracoviensem aedificat, et draco ingens latitans sub arce, incolis onerosus, occiditur". In Dąbrowski, Jan [in Polish] (ed.). Ioannis Dlugossii Annales: seu, Cronicae incliti Regni Poloniae. Vol. 1. Państwowe Wydawn. Naukowe. p. 126 note.

- ^ a b c Plezia (1972), p. 24.

- ^ Kitowska-Łysiak, Małgorzata [in Polish]; Wolicka, Elżbieta [in Polish] (1999), Miejsce rzeczywiste, miejsce wyobrażone: studia nad kategorią miejsca w przestrzeni kultury, Towarzystwo Naukowe Katolickiego Uniwersytetu Lubelskiego [Scientific Society of the Catholic University of Lublin], p. 231, ISBN 9788387703745,

Gdy w w. XVI projektodawcą sposobu uśmiercenia potwora kreowano krakowskiego szewca Skubę (Bielski) [When, in the 16th century, the architect with the means for killing the monster became the Krakow shoemaker Skuba (Bielski), the implausible tale was made to seem true.]

- ^ Bielski, Marcin (1597). "księgi pierwsze: Crakus ábo Krok, Monárchá Polski". Kronika Polska M. Bielskiego. Nowo przez I. Bielskiego syná iego wydána [and continued 1576-86]. Kraków: w Drukární J. Sibeneychera. pp. 29–31.

- ^ Rożek, Michał [in Polish] (1988). Cracow: A Treasury of Polish Culture and Art. Interpress Publ. p. 27. ISBN 9788322322451. (translation of the paragraph from Bielski)

- ^ a b c d Gall, Timothy L.; Hobby, Jeneen (2009). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life: Europe. Gale. p. 385. ISBN 9781414464305.

- ^ a b c McCullough, Joseph A. (2013). Dragonslayers: From Beowulf to St. George. Osprey Publishing. p. 66. ISBN 9781472801029.

- ^ Michajłów, Adam; Pacławski, Waldemar (1999), Literary Galicia: From Post-war to Post-modern : a Local Guide to the Global Imagination, Oficyna Literacka, p. 79, ISBN 9788385158325

- ^ Pleśniarowicz, Krzysztof [in Polish] (2004). The Dead Memory Machine: Tadeusz Kantor's Theatre of Death. Brand, William R. tr. Black Mountain Press. p. 59. ISBN 9781902867052.

- ^ Bandtkie, Jerzy Samuel (1806). "Dratewka". Słownik dokładny języka polskiego i niemieckiego. Vollständiges polnisch-deutsches Wörterbuch (in German). Vol. 1. Breslau: Wilhelm Gottlieb Korn. p. 199.

- ^ Jurkowski, Henryk [in Polish]; Francis, Penny (1996), A History of European Puppetry: The twentieth century, Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, p. 276, ISBN 9780773483224

- ^ a b Hasluck, Frederick William (1929). Christianity and Islam Under the Sultan. Vol. 2. Clarendon Press. p. 655.

- ^ Strzelczyk, Jerzy (2007). Mity, podania i wierzenia dawnych Słowian. Poznań: Rebis. pp. 190–191. ISBN 978-83-7301-973-7. (in Polish), cited by Wiącek (2011), p. 121

- ^ Nungovitch (2018), p. 183 apud Piotr Makuch (2008)

- ^ Plezia (1972), p. 23.

- ^ Wiedemann, Michel (28 March 2009). "Les lièvres cornus, une famille d'animaux fantastiques" (in French). Claude Saint-Girons. Retrieved 2021-12-28., citing Firlet (1996), pp. 150–152

- ^ Kalik & Uchitel (2018) and Nungovitch (2018), p. 183 apud Plezia (1972), p. 25

- ^ Wiącek (2011), p. 121 apud Firlet (1996), p. 96

- ^ Nawotka, Krzysztof (2018). "Syriac and Persian Versions of the Alexander Romance". In Moore, Kenneth Royce (ed.). Brill's Companion to the Reception of Alexander the Great. BRILL. p. 534. ISBN 9789004359932.

The episodes known exclusively from the Syriac A[lexander] R[omance] are that of Alexander killing a dragon by feeding it with oxen filled with gypsum, pitch and sulphur,..

- ^ Miezian, Maciej [in Polish] (November 2014). "Smok wawelski. Historia prawdziwa i wbrew pozorom całkiem poważna". Nasza Historia Dziennik Polski (in Polish). 12: 1–13. ISSN 2391-5633

- ^ Szałapak, Anna (2005). Legends and mysteries of Cracow: from King Krak to Piotr Skrzynecki. Rafał Korzeniowski (photography). Muzeum Historyczne Miasta Krakowa. pp. 190–191. ISBN 9788389599070.

- ^ Wiącek (2011), p. 121 apud Strzelczyk (2007)

- ^ Strzelczyk, Jerzy (1987). Od Prasłowian do Polaków. Kraków: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza. pp. 75–76. ISBN 83-03-02015-3. (in Polish); also cited by Wiącek (2011), p. 121

- ^ Derwich, Marek [in Polish], ed. (2005). "(Recension) Archanioł i smok. Z zagadnień legendy miejsca i mitu początku w Polsce średniowiecznej, Czesław Deptuła, Lublin 2003". Quaestiones Medii Aevi Novae. 710: 386.

- ^ Bielski, Marcin (2003). "księgi pierwsze: Crakus ábo Krok, Monárchá Polski". Archanioł i smok: z zagadnień legendy miejsca i mitu początku w Polsce średniowiecznej. Lublin: Werset. pp. 79–86. ISBN 9788391785638.

- ^ Rożek, Michał [in Polish] (1996). Cracow: city of Kings. Birgit Helen Beile (tr.); Janusz Podlecki (photog.). Prisma Verlag GmbH. p. 73. ISBN 9788386146710.

- ^ Gunn, John (2004). Encyclopedia of Caves and Karst Science. Taylor & Francis. p. 693. ISBN 9781579583996.

- ^ Bielowicz, Marcin (2011-01-03). "Smok Wawelski :. infoArchitekta.pl" (in Polish). infoArchitekta.pl. Retrieved 2018-05-14.

- ^ Wood, Christopher S. (2008). Forgery, Replica, Fiction: Temporalities of German Renaissance Art. University of Chicago Press. p. 183. ISBN 9780226905976.

- ^ "30 lat RMF FM : Matylda". 30lat.rmf.fm. Retrieved 2022-02-15.

- Bibliography

- Anonymous; et al. (Nakł. Akademii Umiejętności) (1878) [c. 1295]. "Chronica Polonorum". In Ćwikliński, Ludwik (ed.). Monumenta Poloniae historica: Pomniki dziejowe Polski [Chronicon Polono-Silesiacum]. Vol. 3. Lwów: Gubrynowicz i Schmidt. pp. 607–609. (in Latin)

- Peter of Byczyna [in Polish]; et al. (Nakł. Akademii Umiejętności) (1878) [c. 1382–1386]. "Kronika książąt polskich". In Węclewski, Zygmunt [in Polish] (ed.). Monumenta Poloniae historica: Pomniki dziejowe Polski [Chronica principum Poloniae]. Vol. 3. Lwów: Gubrynowicz i Schmidt. pp. 430–431(Cap. 3. De Gracco principe). (in Latin)

- Firlet, Elżbieta Maria (1996). Smocza Jama na Wawelu: historia, legenda, smoki. Universitas. ISBN 9788370522926.

- Kadłubek, Wincenty (1872). "Chronica seu originale regum et principum Poloniae" [Całożerca V. Mistrza Wincentego kronika polska]. In Bielowski, August [in Polish] (ed.). Monumenta Poloniae historica [Pomniki dziejowe Polski]. Vol. 2. Lwów: self-published. pp. 256–258 (Liber I: 5–7). (in Latin)

- Kadłubek, Wincenty (1862). Przezdziecki, Aleksander (ed.). Mistrza Wincentego zwanego Kadłubkiem biskupa krakowskiego, Kronika Polska. Translated by Józefczyk, Tomasz. Kraków: wytłoczono u Ź. J. Wywiałkowskiego. pp. 42–43. (in Polish)

- digital copy @ Library of U. Gdańsk

- Nungovitch, Petro Andreas (2018). Here All Is Poland: A Pantheonic History of Wawel. Lexington Books. ISBN 9781498569132.

- Plezia, Marian (1972), "Legenda o smoku wawelskim", Rocznik Krakowski (in Polish), 422: 21–32, ISSN 0080-3499

- Rajman, Jerzy [in Polish] (2007). Kraków: studia z dziejów miasta : w 750 rocznicę lokacji. Wydawnictwo Naukowe Akademii Pedagogicznej. ISBN 9788372714527.

- Schlauch, Margaret (April 1969). "Geoffrey of Monmouth and Early Polish Historiography: A Supplement". Speculum. 44 (2): 258–263. doi:10.3406/slave.2008.7124. JSTOR 2847606.

- Wiącek, Elżbieta (2011). "Smok smokowi nierówny : niezwykłe dzieje Smoka Wawelskiego : od mitycznego ucieleśnienia chaosu do pluszowej maskotki". In Biliński, Piotr [in Polish] (ed.). Przeszłość we współczesnej narracji kulturowej. Tom 1: Studia i szkice kulturoznawcze. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. p. 121. ISBN 9788323383758. (in Polish)